What you'll find out

Digital Technology Vision in the UK

The UK has a strong and healthy technology industry that continues to grow and prove it is essential for the overall economy. The Digital Economy Council valued the UK’s tech ecosystem at $446bn in 2018, but after the Covid-19 pandemic – that accelerated digital transformation – it’s now valued at just under $1tn, placing it third in the world, and it’s estimated to contribute £101.8 billion to the nation’s economy. Almost 5 million people worked in the UK tech industry during 2022, compared to 3 million workers in 2019, with London, Manchester and Bristol being the top three areas for tech employment. Tech employment accounted for approximately 7.6% of the overall U.K. workforce in 2020.

2021 was a record year for venture capital funding, which reached $40.8bn. Fintech (Financial Technology) alone holds 34% of total investments for the year 2021. The UK is also the third ecosystem in the world to have over 100 unicorn tech companies (those valued at over $1bn) and is just under China and the US. There are a total of 123 tech unicorns in the UK, up from 12 in 2012, most of them based in London and spread across various sectors. Fintech is the largest one, with 21 unicorns.

While the UK and Germany have seen significant growth in capital investment, with the UK alone accounting for 35% of total investments in Europe in the past 5 years, their relative share of investment has been decreasing compared to other regions in Europe, like Portugal, Iceland or Croatia.

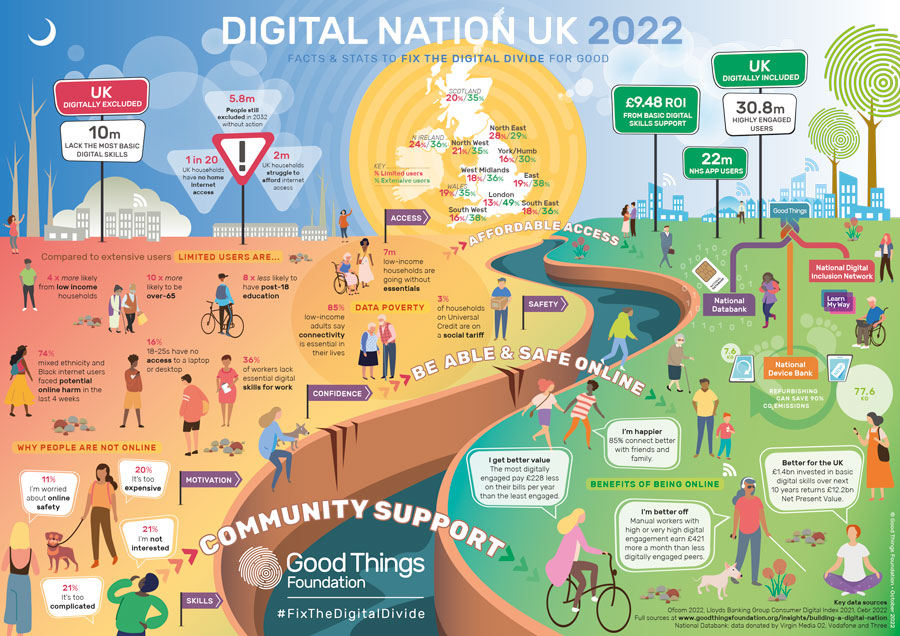

Despite having a growing digital sector, the UK is facing a digital inclusion challenge: one in five people lack at least one essential digital skill needed for everyday tasks, and 2 million households struggle to afford internet access. This gap in basic digital skills means that a large number of adults in the UK can’t turn on a device, interact with it, communicate with others digitally, or understand that not all online information and content they see is reliable.

These are only a few examples of the essential digital skills framework developed by the UK government in 2019 to support digital literacy across the UK. Digital exclusion can also affect children and their future; according to Digital Poverty Alliance, 1 in 5 children did not have access to an appropriate device like a laptop while homeschooling during the covid-19 pandemic.

This infographic, created by The Good Things Foundation– the UK’s leading digital inclusion charity- illustrates a map of the UK’s digital inclusion and exclusion landscape.

The Covid-19 pandemic has not only accelerated digital transformation but has also widened the gap between those who have access to technology and those who don’t. According to the 2022 Lloyds Bank Consumer Digital Index, 41.9 million adults in the UK today have the Essential Digital Skills they need for day-to-day life, and 11.0 million are digitally disadvantaged, lacking Essential Digital Skills for Life.

The UK’s Digital Strategy: challenges and opportunities

In June 2022, London hosted the anticipated annual Tech Week (https://londontechweek.com/), where key tech industry stakeholders gathered to celebrate the industry’s success and look to the future. In this year’s event, the Government also played an important role, releasing a much-awaited Digital Strategy Paper (the last one was published in 2017). This policy paper aims to create a guideline for the UK’s future digital transformation and digital economy, assessing how the UK’s digital industry is currently standing and setting goals for the future. The report starts with a powerful statement from the Minister for Tech and the Digital Economy, Chris Philp:

The UK’s economic future, jobs, wage levels, prosperity, national security, cost of living, productivity, ability to compete globally and our geo-political standing in the world are all reliant on continued and growing success in digital technology. That is why the UK must strengthen its position as a global Science and Tech Superpower – and why the Government is taking steps to achieve it.

This report praised the UK’s strong international position in the tech industry, with a «flourishing» digital sector. Some of the UK’s strengths that have made this growth possible are:

- a strong data economy which made up around 4% of the UK’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020,

- an improved digital infrastructure with superfast broadband coverage for over 97% of UK premises,

- and a thriving startup scene that is known for having the most significant number of unicorn companies in neighbouring countries. Venture capital investment is a big part of this strong startup community, reaching £27.4 billion in investment in 2021. Here you can find a list of the UK’s top startups, updated in late 2022.

Facing the future, the UK’s Government plans to strengthen four pillars on which a new and vibrant digital economy can grow into a superpower: a robust digital infrastructure, a data-based economy, a new regulatory framework and a secure digital environment. These four pillars form the foundation of the UK’s new digital strategy, which relies on six areas of improvement:

- Digital Fundations: establishing a robust infrastructure to support nationwide gigabyte coverage is critical to maintaining and growing a digital economy throughout the country. This infrastructure development goes hand-in-hand with developing a modern data regulatory regime that helps the UK become the strongest data economy in the world. Working towards this goal, the UK’s government has created a new Central Digital and Data Office, recruited a new Information Commissioner, sealed data flow agreements with the EU and Japan, and established a Digital Market Unit to oversee future digital markets.

- Ideas and Intellectual Property: stimulating and funding research and development in education can lead to a growing pool of experts and talent that will grow the technology industry of the future. The United Kingdom Research and Innovation Organization has added £18 billion of value to the UK economy since 2007, accelerating innovation, helping organisations create over 70.000 jobs and funding research in academia and business. An important part of transforming ideas and innovation into economic growth is helping universities turn academic research into commercial solutions to feed the private sector with ideas and creativity. Innovation is also needed in the public sector, with a particular focus on the NHS.

To achieve its goals, the UK’s government has announced an increase in public R&D, spending up to £20 billion by 2024/25. They have also promised to increase funding for HEIF (Higher Education Innovation Funding) from current levels of £250 million per year to support universities spin-offs and up to £200 million committed to support NHS-led health research into diagnostics and treatment.

-

Digital skills: helping develop digital skills across the UK can improve the “digital skill crisis”, which is estimated to cost the UK economy around £63 billion per year in the lost potential gross domestic product (GDP). One of the first steps in alleviating this talent and skill shortage is strengthening digital education in schools and universities, offering high-quality tech education. It is also critical that individuals educated in digital skills are aware of the career opportunities available so they feel inspired to pursue jobs in the tech industry.

In an effort to slow down the digital skill crisis, the Department for Education is investing more than £750m over the next three financial years (2022-23 to 2024-25) to support high- teaching and facilities in higher education (HE). The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) is funding 2,000 scholarships to be delivered between 2023 and 2025 and funding for 1,000 PhD places in AI through 16 Centres for Doctoral Training.

-

Financing digital growth: The UK tech sector raised £27.4 billion in private capital during 2021, which is double the amount of Germany and triple of France. 2021 was also a good year for the London Stock Exchange (LSE), which saw £16.9 billion raised through initial public offerings (IPOs) alone, the most significant sum since 2007. It is currently the number one exchange in Europe. The UK’s government plans to encourage top innovators to go public in the UK. The Financial Conduct Authority reforms make the listing regime, the criteria to be allowed to list shares in the UK, more effective and manageable, hoping to attract more investment.

- Spreading prosperity across the UK: Digital adoption across industries and sectors supports companies to innovate, reach new markets and gain productivity. The biggest challenge for SMEs (Small and medium-sized enterprises) to navigate is learning to identify the best solution for their needs and understanding how a technological solution could help them grow. Digital transformation is not only necessary for companies; public services have also undergone a digital transformation process over the last few years and continue to need progress in their adoption of technological solutions. An excellent example of this public transformation could be the Making Tax Digital (MTD) programme, that helps businesses file taxes and avoid mistakes, or the One Login registration for Government.

To help facilitate tech adoption in business, DCMS launched Digital Boost, which matches small businesses and charities with a network of digital experts. The Government has also invested more than £147 million into the Made Smarter Innovation programme (https://www.madesmarter.uk/) to help boost tech adoption. The Help to Grow programme provides tech education and advises companies on their tech adoption process, helping them obtain financing for technology solutions.

-

Enhancing the UK’s place in the world: the connection between global leadership and the digital economy is now more vital than ever. Digital technology’s geo-political importance continues to grow as governments show their global influence through their technological power. The UK also intends to continue working with the OECD, the G7 and the UN, shaping international standards for tech regulation and seeking international agreements. The UK has signed trade deals as an independent trading nation with Japan, Australia, Singapore and New Zealand. These deals give UK firms better opportunities to trade digitally with these markets. There is also a commitment to strengthen UK-US tech partnership.

A Data Economy for the future: Infrastructure and data regulations

Keyword: Data

For this section of the report, the data definition is especially relevant, considering it is a concept known for being difficult to define. The UK’s government works with this current definition of Data:

“When we refer to data, we mean information about people, things and systems. While the legal definition of data covers paper and digital records, the focus of this strategy is on digital information. Data about people can include personal data, such as basic contact details, records generated through interaction with services or the web, or information about their physical characteristics (biometrics) – and it can also extend to population-level data, such as demographics. Data can also be about systems and infrastructure, such as administrative records about businesses and public services. Data is increasingly used to describe location, such as geospatial reference details, and the environment we live in, such as data about biodiversity or the weather. It can also refer to the information generated by the burgeoning web of sensors that make up the Internet of Things”. (National Data Strategy Policy Paper, 2020)

A big part of the UK’s plan to grow into a world-leading tech superpower relies on creating a robust data economy. This is achieved when data is collected, processed and exchanged across a large digital ecosystem with the purpose of extracting value from the collective information. Data is continuously growing and shaping our markets; it fuels innovation which results in rapid advances in areas like machine learning, AI or improving the efficacy of public services. A data-driven economy is complex and presents many ethical and economic challenges. Still, it is bringing many opportunities for countries to establish themselves as economic giants, much like oil production played an important role in creating economic power players over the last century . Currently, the list of top data-driven economies is led by the US, followed by the UK and China.

The UK’s government plans to not only hold its current position in the global map of data-driven economies and new tech data leaders but to encourage the growth of data-fueled innovation, collection and exchange. This cannot happen if people – consumers, users and data producers – don’t have access to the internet. The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) claims to be working hard on a program that will ensure national gigabit broadband and hopes to achieve 99% coverage by 2030. This infrastructure will help support a healthy data-based economy, where businesses and people can use data in their day-to-day lives to push the economy forward. The DCMS has announced its plans to reform the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to enable innovation while keeping an open flow of personal data from Europe.

The DCMS also focuses on the importance of regulating secure digital identities that can be used to make everyday digital transactions easier and safer and improving people’s experiences, privacy, access to services, and reducing fraud .

TechUK, the UK’s leading technology membership organization, applauds the government’s efforts in recognizing the importance of data for the UK’s economic growth but points out some missing pieces in its Digital Strategy concerning data policy.

One example they reference is the need for open public sector data sets for commercial use, using the publication of Transport for London live data as an example, which is mentioned in the Digital Strategy Paper (page 18). This live data, published in 2017, boosted the creation of user-centred products and services that resulted in less congestion and reduced commute times on public transport. TechUK hints at how other open public data sets can help stimulate innovation by not having to rely solely on private organisations for data production .

At the end of 2020, The UK published a National Data Strategy Policy Paper in which they elaborated extensively on the importance of harnessing the power of data to transform the country. They identify five different opportunities for transformation:

- Boosting productivity and trade

- Supporting new businesses and jobs

- Increasing the speed, efficiency and scope of scientific research

- Driving better delivery of policy and public services

- Creating a fairer society for all

To transform each of these areas truly, they acknowledge the fact that data needs to be “usable, accessible and available across the economy” (NDS, section 3). This approach is not problem-free, and the Policy paper makes a somewhat detailed analysis of the implications of creating available data across the country:

This is not simply a case of opening up every dataset. We must take a considered, evidence-based approach: government interventions to increase or decrease access to data are likely to have myriad consequences, intended and not. There is a balance to be struck between maintaining incentives to collect and curate data, and ensuring that data access is broad enough to maximise its value across the economy. For personal data, we must also take account of the balance between individual rights and public benefit.

This complex issue brings forward the necessity to develop a policy framework that sparked a Government Consultation on National Data to open a conversation about how the UK can use and create data. This consultation took place between the 9th of September and the 9th of December of 2020. Tech companies, think tanks, academics, public organizations and citizens participated in the process and sent over 250 responses.

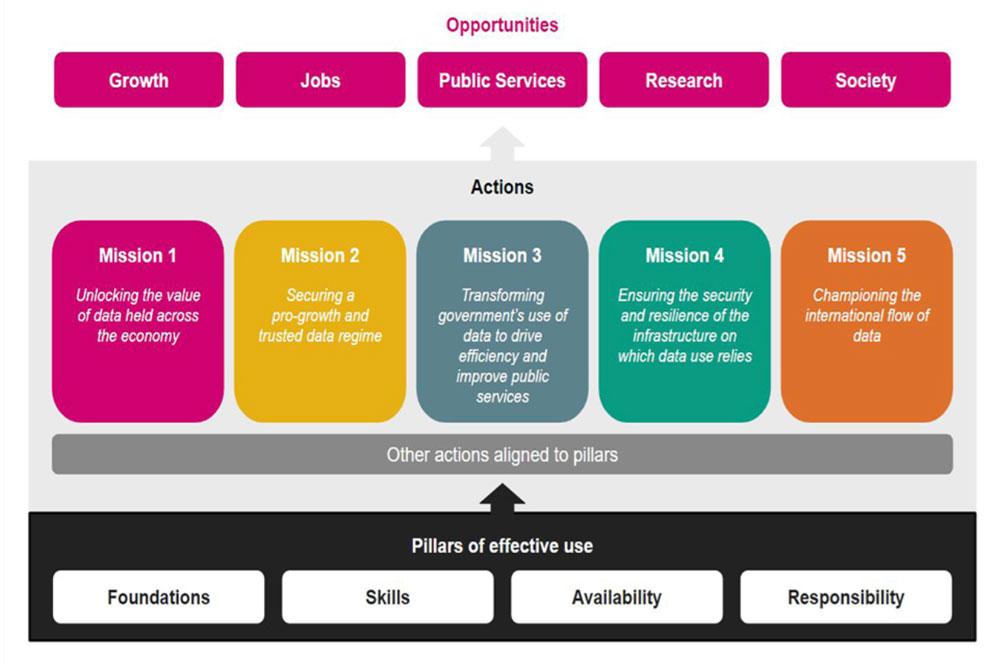

These responses resulted in a mission plan for the Data Strategy with five clear statements:

Mission One: Unlocking the value of data held across the economy. Some key actions mentioned as a part of this mission are: establishing a Digital Market Unit to oversee future digital markets, researching data ethics and availability, and building data literacy across the economy.

Mission Two: securing a pro-growth and trusted data regime. This includes recruiting a new Information Commissioner and a programme to improve data sharing.

Mission Three: Transforming the government’s use of data to drive efficiency and improve public services. Some key actions are creating a new Central Digital and Data Office, publishing guides for metadata standards or data control, or training 500 public sector workers to use Data Science skills.

Mission Four: Ensuring the security and resilience of the infrastructure on which data relies. The National Security and Investment Act can now intervene in transactions to protect national security.

Mission Five: Championing the international flow of data. This includes data flow agreements with the EU and Japan and reciprocal free flows of personal data with all non-EU countries that the UK recognises as adequate.

Overall, the UK’s data strategy can be summarized as an attempt to establish itself as a strong and stand-alone superpower, separate from Europe’s data guidelines but remaining internationally connected to other markets.

The strategy shows a clear intent to maintain a strong position in the global data market and ambitiously looks forward to a future when the UK can be recognised as the top data-driven economy.

(National Data Strategy Policy Paper, 2020)

Workplace gap: existing problem between supply and demand in digital technology

Rapid digitalisation has made work-related digital skills essential. The fast development of technology and the problem the workforce is facing to keep up with the advances is called “the digital skill gap”: the tech industry demands more skilled workers to sustain its growth, but the workforce is unable to meet the demand.

This gap has been a global problem for many years, but with COVID-19 accelerating digital transformation, it has never been more profound. The impact of this gap is not only problematic for the tech industry; it is now apparent across industries as digital skills become increasingly necessary for all sectors impacted by the consequences of COVID. The impact of the gap is not just economical either: digital skills are more and more essential for day-to-day activities or education. A workforce with inadequate digital skills slows down innovation and productivity.

Basic digital skills are now crucial to everyone across industries and occupations and are the ones we can consider foundational. These basic skills can be defined as having a minimum level of competency in digital communication, problem-solving, handling information or being safe online. They can also include being comfortable using standard software such as Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, email or search engines.

The demand for workers with advanced digital skills is growing, and the gap between supply and demand is worrying. Unlike basic digital skills, these do not affect everyone across sectors: they are more specific and limited to the tech industry. These advanced skills involve good knowledge across areas such as computer design, coding or specialist software.

Have we got the necessary skills to work in tech?

The Essential Digital Skills Framework is a guideline led by Lloyds Bank, in partnership with Ipsos MORI, supported and funded by the Department for Education and Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. Since 2018, Lloyds Bank has published an annual digital skills report in which they present three different levels within the framework to analyse the UK’s adult digital education:

- The Foundation Level

- Life Essential Digital Skills (EDS)

- Work Essential Digital Skills (EDS)

The basic seven digital skills needed for everyday life make up The Foundation level: use the different menu settings on a device to make it easier to use, find and open different applications/programmes on a device, update and change a password when prompted to do so, turn on a device and log in to any accounts/profiles, open an Internet browser to access websites, utilise the available controls on a device and connect a device to a Wi-Fi network. Adults who can’t perform any of those seven tasks by themselves are digitally excluded.

For Life and Work EDS there are five skill areas (communicating, handling information and content, transacting, problem-solving, being safe and legal online) with 29 specific tasks within Life and 17 tasks in Work.

The covid-19 pandemic encouraged programmes, initiatives and people to tackle issues around digital exclusion faster and better, resulting in 1.9 million fewer people who are digitally excluded than before the pandemic.

However, in 2021, nearly 10.0 million people (19%) cannot complete all fundamental digital skills and are partly excluded from the digital world. 2.8 million people (6%) aren’t able to complete any of the foundation tasks and therefore are entirely digitally excluded.

Those who are entirely digitally excluded and can’t participate in the digital world at all share some data points that help us visualise a profile for digital exclusion in the UK: aged 75+, living alone, not working, no formal education, Living with a sensory impairment and lowest social grades (DE).

The Lloyds Bank report finds interesting data regarding the workforce: “approximately 11.8 million (36%) of the workforce lack Essential Digital Skills for Work. 8% of the workforce lack the Foundation Level (the very fundamentals of connecting to the Internet) and whilst a further 7% have achieved this level, they lack any workplace digital skills” (Page 4). This means that one-third of the workforce is yet to power up.

This data is an improvement if we compare it to other years: 5.6 million more working adults have the skills needed to thrive in UK workplaces than in the year before.

According to the Nominet Youth Index, 20% of young people do not feel they have the basic training in digital skills. Despite this, over half of them (57%) want a job that uses advanced digital skills like, for example, coding. However, it’s interesting to note that this level of interest in digital careers doesn’t seem to be reflected in the number of people choosing IT as a subject in school or choosing tech-related studies after school. The Learning and Work institute shared data on the number of students taking IT at GCSE has dropped by 40% in the last seven years, and the number of young people taking A-levels or further education courses in IT is also declining. This data might be explained by the fact that young people expect employers to provide in-job training, yet almost half the employers surveyed in that study claimed they couldn’t offer training.

A report called Disconnected?, by Wordskills UK and the Learning and Work Institute, states that the digital skill crisis can affect young people in acquiring advanced skills but not the basic ones.

Young people in the UK considered “digital natives”, don’t experience many problems with essential digital skills but do not feel comfortable in their advanced skill set.

Talent shortage: a problem to solve

It seems contradictory that the UK’s tech industry is simultaneously experiencing growth and a talent shortage. The industry is at an all-time high, and yet, according to Tech Nation People and Skills Report 2022, there were two million vacancies in tech during 2021, more than in any other industry.

According to this same study, tech salaries in the UK are, on average, a lot higher than in different sectors and over 36% of jobs in the tech industry are non-tech occupations (HR, Sales or Managers). These insights make explaining the talent shortage difficult, yet according to Nesta’s skill report, the talent shortage is costing the UK economy £2 billion a year. The demand is there, but what about the talent?

In 2017 the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee published a report called “Digital skill crisis” that states that the skill gap, present in all stages of the education pipeline, was creating severe issues in the workforce—from workers not being able to adjust to rapid changes in their industries to young people not being aware of job opportunities that require digital skills.

This report paid particular attention to the importance of adapting the school curriculum to new times, acknowledging that schools must ensure that students are trained in skills that will enable them to participate in the digital economy in the future.

This, of course, is an impossible task if teachers are not digitally qualified themselves and that presents the need to upskill teachers, helping them keep up with technology and making sure they are prepared for the digital age. This report also notes the importance informal learning has in the younger generations.

In the Nominet Youth Index survey, 51% of participants claim to have learnt digital skills by themselves using tools like Youtube and other websites. Young people look for alternative solutions, programmes or sources to learn the skills they feel are needed for the future.

The industry requires a skilled workforce now, however. The Tech Nation People and Skills report 2022 claims that the demand for senior roles in the tech industry is growing rapidly and it outweighs the market for entry-level jobs, but the number of experienced candidates is small compared to the number of people with “no experience” looking for vacancies. This situation creates an imbalance in the number of people available for specific roles, which becomes a frustration for employers.

The Employer Skills Survey found that nearly one in three skills shortage vacancies in 2019 was due to a lack of digital skills. Furthermore, 24% of employers say they struggled to recruit workers with basic digital skills, and 41% have struggled to recruit workers with advanced digital skills. Close to half of employers surveyed are offering in-job training as a strategy to palliate the gap.

Reskilling and upskilling employees is an effective tactic to address skills shortages, but it comes with challenges. Reskilling and upskilling programmes can be hard to run not just from a practical point of view but also because they involve high doses of cultural change inside a company, which is notoriously hard to manage.

One of the first challenges a company faces when it starts a re-upskill programme is the prioritisation of new skills to address and the selection of which employees to reskill. A more significant challenge is to develop strong capabilities in curriculum design or understanding employees’ incentives. A considerable part of reskilling is understanding how to redesign jobs and tasks that will become automated in the next few years, and that is no small undertaking.

This transition is challenging across industries, and it’s difficult to predict and understand for many companies that are experiencing the shift on a day-to-day level. On the one hand, it may be easier to identify the tasks or jobs that are being displaced by automation but it’s more challenging to identify the potential new jobs created as a result of this economic transformation.

The UK’s exit from the European Union has impacted the current skill gap crisis, creating a tense atmosphere for companies looking to attract talent and people looking for opportunities. Brexit is not the cause of this talent shortage, but it has exacerbated its impact on the industry, making it harder for companies to recruit new talent. Before Brexit, UK tech companies could efficiently recruit workers from other EU countries, which allowed them to access a large pool of talented individuals. However, since the UK decided to leave the EU, recruiting workers from the EU has become more complex and time-consuming, making it more difficult for companies to access the talent they need.

According to the Migration Observatory, work was the most important driver for overall migration, accounting for 40% of migrants moving to the UK from 2010 to 2019. For the last two decades, the EU has been the primary source of work-related migration.

Since the Uk’s exit from the European Union, EU citizens are no longer able to move to the UK without a visa and freedom of movement for UK and EU citizens was replaced with a points-based immigration system, which means that companies have to go through a more complex process in order to hire workers from the EU. The process now includes obtaining a sponsor license and complying with a range of other requirements, which can be time-consuming and costly.

One of the biggest challenges UK tech faces now is how to engage with talent outside the UK. Even if a company is able to obtain a sponsor license and comply with immigration rules, it may still face challenges in accessing the talent it needs. Due to the increased bureaucracy and uncertainty associated with Brexit, many EU workers may be deterred from coming to the UK.

Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic are largely entangled, and separating the impacts of the end of free movement from other consequences or complexities of the post-pandemic market is very difficult.

Gender gap. How big is the gender gap in the digital tech industry, and how is it affecting the sector?

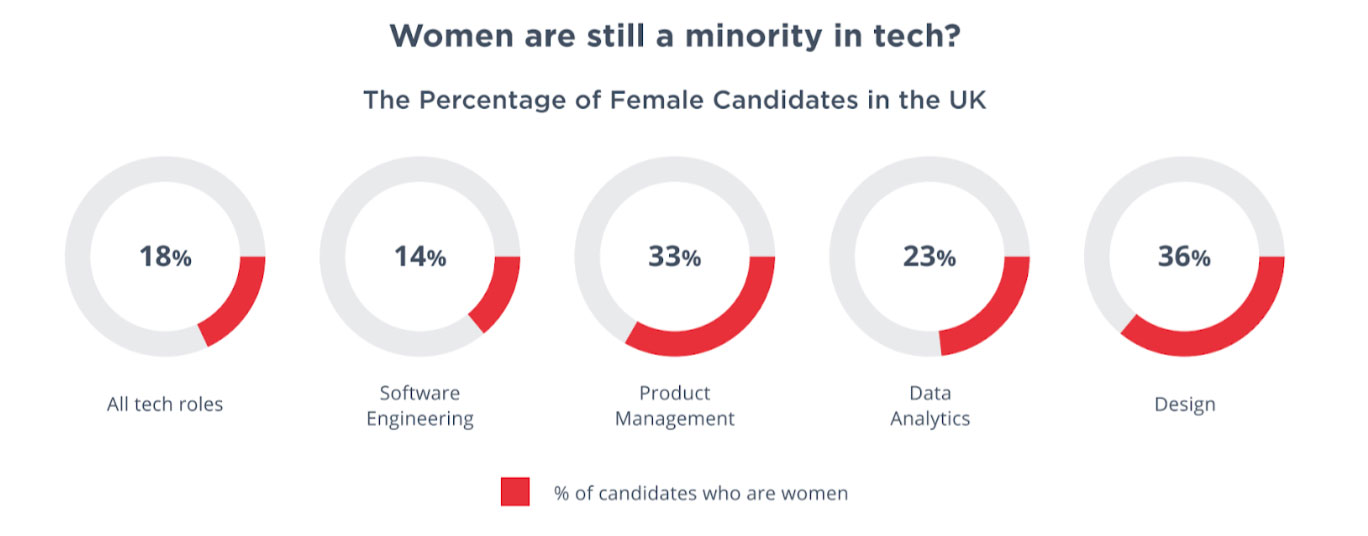

With an industry that employs almost five million people in the UK, only 17% of tech occupations are taken by women, yet women account for 49% ok UK’s workforce. This enormous difference in the data between women working overall and women working in the tech industry is what we call the Gender Gap.

The underrepresentation of women in technology is an issue that starts before people are ready to join a company; it’s already an issue by the time students are prepared to choose a career pathway.

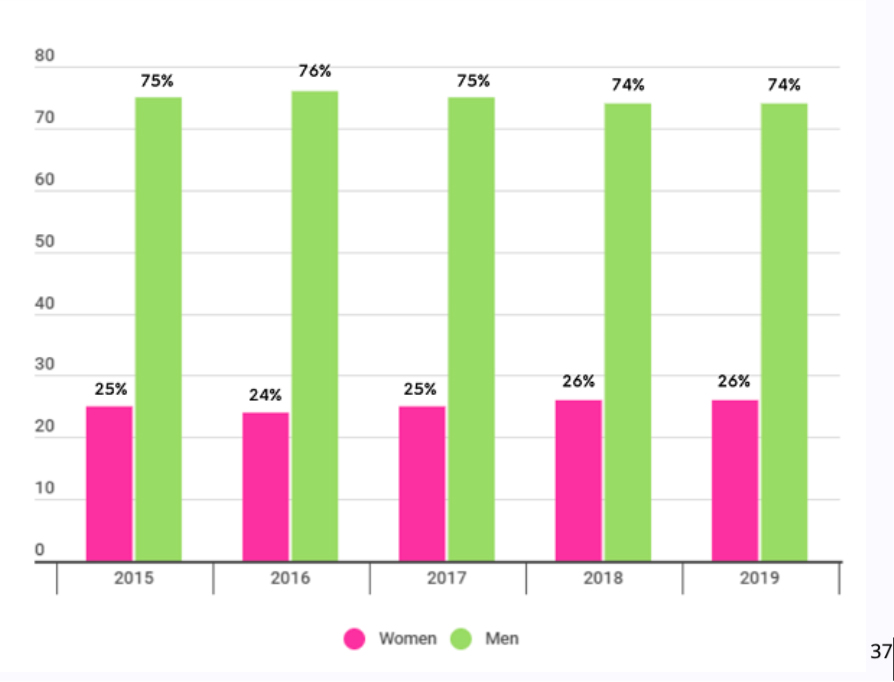

According to the Women In STEM 2019 “Understanding the gender imbalance in STEM” report, 35% of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) students in higher education in the UK are women. From 2015 to 2019, we can see an increase in the number of women graduating from STEM, but considering the more rapid growth in the number of men graduating from these subject areas, the percentage of women has fluctuated very little and staggered.

Percentage of Males and Females graduating from STEM subjects :

In a 2017 research report, PwC UK found three main themes that help understand the gender gap in tech, where it starts, and how we can address it effectively.

- Girls are less likely to study STEM subjects at school – and this gap continues through to university. Understanding what is behind girls’ decisions not to choose STEM subjects in school is incredibly complex. Part of the issue could rely on the lack of motivation from the tech industry itself, which is failing to show young girls there is space for them. Another issue that plays into this is teachers’ lack of understanding of the tech industry and the jobs or outcomes a career in the sector can provide. The result is that girls are not getting the correct advice or inspiration from the school itself. In this study, 33% of male respondents say they’ve had a career in technology suggested to them, compared to just 16% of females.

- Females are less likely than males to consider a technology career: when girls in school look ahead and plan their future, most don’t seem to consider tech an option. In the research, 53% of girls say their preferred career was a factor in their choice of A-Levels, compared to just 43% of boys. Without the proper guidance and advice, girls planning for their future careers can choose subjects that are unrelated to tech early on.

- A shortage of female role models is a significant barrier – as is a lack of understanding of how technology can enable women to change the world. Representation is critical to imagining yourself in the future and feeling inspired to follow a path others have shown you. In this study, when asked to name a role model who has inspired them to pursue a career in technology, 83% of female respondents said they couldn’t think of anyone.

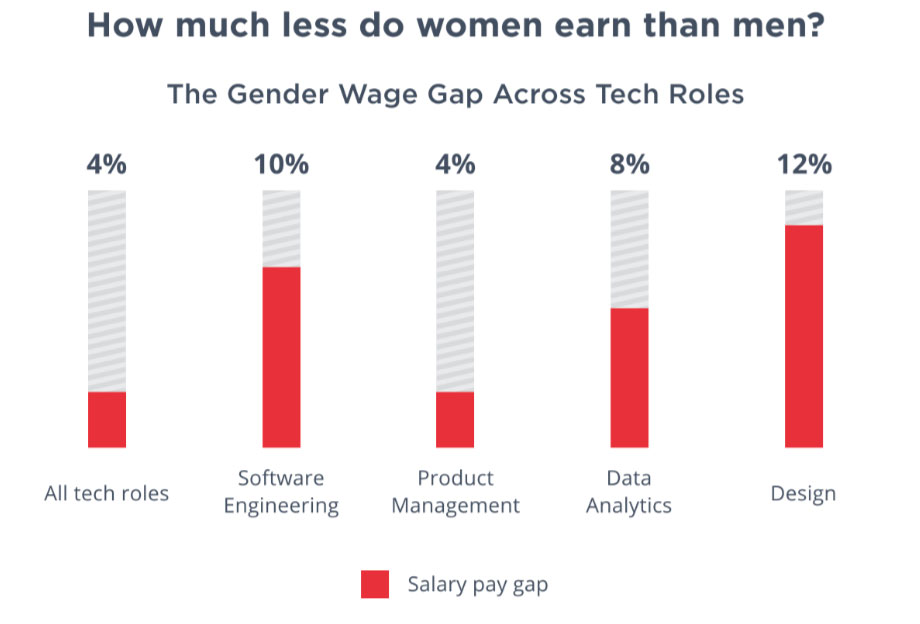

The result is that women are underrepresented in the tech industry across fields, are less likely to occupy leadership roles and receive less funding to build a business. In the UK, female talent receives 4% less salary on average than men. The UK tech workplace equity report by Hired does a great job translating this statistic into comprehensive data:

“These figures are even more impactful when translated into cash value. The average salary offered to male tech workers is £66,000 and the average salary offered to women is £63,000. The gap between these figures is a jarring £3,000, which is £250 pounds less in their paycheck every month.”

The UK Tech Workplace Equality Report.

This graph, from the same study, helps put the economic gender gap into perspective:

And, according to WomenTech Network, we are still various generations away from closing this gap. Women are less likely to join tech careers and, at the same time, are given fewer opportunities to stay or grow.

Gender imbalances, toxic work culture or direct discrimination are systemic issues in the industry that contribute to women deciding not to stay in the tech sector or not advancing in their careers. A survey found that 20% of female respondents have resigned from a role because of discrimination or harassment and in an industry where 3 in 5 women have felt discriminated against in the workplace because of their gender, it becomes clear the issue is largely impacting the industry itself.

A member of a leading tech organisation that empowers women and girls to join the tech industry, S.M., has first-hand experience fighting gender imbalances as a tech founder and software developer. S.M. now leads a successful team of women offering IT and development services, and their clients are usually other female-led companies. A core mission of S.M’s brand is contributing to a female tech community where supporting others’ growth means actively addressing the gender gap and the lack of diversity in the industry.

“We all thrive in a community where more women start a business or are happy in their job. I don’t want to have a company in an industry where I’m the only woman and (…) most women I know would agree. We all need to feel a sense of community and togetherness because we know that that is how we grow, feel safe and inspire other people”.

According to the Hired report, women are currently underrepresented in most areas of the digital tech industry. As S.M. describes, the lack of women in the industry deters others from joining as the social and emotional incentives might not be there for them.

Graphic from The UK Tech Workplace Equality Report

S.M. also spends a lot of her time mentoring women entrepreneurs, career changers and STEM students. Is in her mentoring role that S has gained an in-depth understanding of the challenges women face in her industry.

“There is a lot of hypocrisy in tech, lots of companies say they are inclusive but you look at management and there are no women (…) they only talk about other men. It’s a hard climb and ofter women don’t even get the chance”

She talks about her role as an empowerment mentor: helping women gain confidence to apply to jobs, ask for the salary they want, speak up when they face harassment or other issues and start their own companies. She recognises that many of the great issues women face in tech are systemic and can’t be solved by women’s individual choices, but that helping other women face up these challenges is how she can contribute to making the industry a better place.

As S.M. points out, the lack of women in tech, both in leadership positions and technical roles, undermines not only the industry but also the economy’s potential. The lack of diversity in the tech industry has been linked to a lack of innovation and a less inclusive culture. This is why it is crucial that the industry as a whole takes a proactive approach to address these issues to ensure that the workforce of the future is truly diverse and inclusive.

The training offered by Ironhack to alleviate this problem (experts)

Ironhack celebrated its first UK campus in London in march 2022 with an event focused on the future of education, closing the gender gap and improving digital skills.

Since that first launch, the UK campus has become a very international environment.

Gabriel Pizzolante, growth manager in the UK team, defines the right strategies and channels to get consumers to learn about Ironhack. As a self-described previous non-techie that has been working in the tech industry for over seven years, he has seen the industry grow and change. Bootcamps are valued, and career-changers have many opportunities to retrain.

When talking about Ironhack UK, Gabriel mentions that “by only offering Remote bootcamps in the UK, we have a very diverse pool of students (…)The bootcamps are also run for Europe, so it’s a very international experience. This brings diversity to the online classroom bringing different perspectives to the projects they work on and the learning environment.”

Ironhack UK offers students a unique opportunity to study remotely, get to know other international students and develop their careers. According to Gabriel, most UK students join Ironhack looking for “a rewarding career and more opportunities to progress. Their goals include to become financially independent, to have more freedom to choose what they want to work on, and have better opportunities available”.

Ironhack actively contributes to closing the gender gap in the UK tech market. In their first year, Ironhack UK had 60% male and 40% female students, and they continue to focus on supporting and encouraging more women to train in tech.

Supporting students on how to approach interviews, build their CVs and portfolios and develop key soft skills to enter the job market successfully is a big part of what sets Ironhack apart. Ironhack is actively working towards alleviating the pressure of the skill shortage by understanding how career-changers and other students are facing the next steps in their careers and helping them get through the process. Offering the right tools, hard and soft skills, is critical to help reduce the skill gap in UK’s tech scene, and Ironhack is actively working towards this ambitious goal.

What do experts say?

Dr Zhichao is a project and research manager in a large innovation consultancy based in London. Coming from a physics background and previous experience working in innovation research where he had first-hand experience using and experimenting with cutting-edge tech and state-of-the-art equipment and analysis methodologies, Zhichao now has a panoramic view of the tech industry from two very different sides: how innovation is technically achieved and how companies implement it.

During our interview, Zhichao focused on the management aspect of his role, talking about how team management has changed in the last few years. The most obvious change he has perceived is how people now expect to be able to work from home and use the office as an in-person work-social space.

“I think it’s mostly that we realised… everyone realised … that we were still productive at home and more comfortable and the flexibility made a change. Working from home requires trust and self-awareness but the benefits are there (…) now we feel it’s normal”

People have turned to hybrid work to gain a healthier work-life balance, but this work shift comes with a unique set of challenges. For example, in a UK survey, 69% of employees claim to feel worried that their employer will not adapt their workplaces, policies, or in-office requirements for hybrid work. Zhichao believes that there is where new social soft skills come in handy. Communication, attention to detail and empathy are the ones he pays special attention to during our conversation. Hybrid work requires management and teams to strengthen their soft skills, to avoid developing issues that are harder to manage over an email or video chat.

“Being resilient and willing to work with different people, spotting problems and being quick to solve them as you go… those are the qualities that make the difference if you want to work in tech”

- is a manager at one of the biggest tech companies in the world, and she works from the London Head Quarters. With a background in UX and Cultural Anthropology, she now leads a team and is responsible for brand cultural growth.

- shares some ideas and perspectives with Zhichao on how management is changing and adapting to new times, and during our conversation we also spend a long time chatting about how to adapt offices and physical spaces for a workforce that spends less time there:

“versatile work stations, having light-filled floors, preparing some spaces for social events… just so we can have a chat and connect (…) a lot of innovation happens through collaboration and people connect on another level when they can spend time with each other”.

For W., it’s not about networking events or outings but more about making people feel welcome and comfortable working from the office. According to W., workers should feel they go to the office with a purpose: getting to know co-workers, having creative sessions or collaborating with others. Reinforcing these elements of in-person work can help create a space that facilitates innovation and team growth without pressuring people to work from the office when they have other priorities.

Diversity was another hot topic in W.’s and Zhicaho’s interviews. Zhichao works in an interdisciplinary environment and claims that innovation-based teams need this disciplinary diversity in order to work correctly. He notes that he has also experienced a lot of racial and ethnic diversity throughout his career, although he feels gender diversity is still prevalent.

Perhaps Zhichao’s experience with ethnic diversity is somewhat unique, as the industry has been extensively called out for its lack of diversity and representation. Dr Anne-Marie Imafidon, a well-known advocate for diversity in tech, recently published her first book, titled “She’s in CTRL”, where she insists that technology is not a constant force, it’s constantly changing and adapting. It’s also not for a few privileged people, it’s within our reach. She encourages everyone – but especially those that the tech industry considers minorities to participate in decision-making processes actively.

In the chapter “Holding Tech Accountable”, Anne-Marie Imafidon writes:

“When we’re building a system that makes decisions on human beings, it’s important for all human beings to be acknowledged in its creation. We all need to be a part of making the right kinds of technical decisions and in understanding the decisions that are being made about us.”

A.H. is the founder of a firm that helps companies improve their inclusivity, fight against biases and create environments that foster diversity. She also travels the world as a keynote speaker and shares her thoughts on how inclusivity can future-proof a company’s legacy. A.H. is clear when she says, “Tokenism is not the answer”, and it won’t save tech from its diversity issues.

Tokenism refers to the practice of making only a token effort to include a diverse group of people in a given field or industry, without making any real changes to the culture or systems that perpetuate inequality. In the tech industry, tokenism can manifest in the form of hiring a small number of underrepresented individuals as a way to appear diverse, without actively working to create an inclusive and equitable environment. This can include things like creating diversity quotas, offering diversity training, not addressing the underlying issues that are causing the lack of diversity, and not providing the necessary support for underrepresented groups to succeed in the industry. Tokenism is often seen as a superficial and ineffective way to address diversity and inclusion issues rather than a comprehensive approach that addresses the underlying issues.

Aside from diversity and inclusivity, W. also expressed how public opinion is becoming a big trend in the tech industry, and she expects it to become more relevant in the coming years. Public participation and social debates, according to W., are critical as they help to ensure that the industry is transparent, accountable, innovative, inclusive, and responsible in its development and implementation of digital technology.

Experience of employees with Career Changes

Over the last few years the phenomenon dubbed “the great resignation” is changing the job market across countries, impacting how people are choosing their next work-related change or their motivations for staying in their current job or industry.

This trend is complex and multifaceted, and it can be considered a cultural transformation event due to the impact it is currently having on workers’ mindsets and how companies are approaching recruitment. Some of the many reasons we can consider key in understanding this market transformation are the importance given to company culture and alignment to company values, the rise of remote work, prioritising work/life balance or the availability of other attractive vacancies.

According to a Statista report, 365,000 job-to-job resignations took place in the United Kingdom in 2022’s third quarter, compared with 442,000 in the previous quarter, which seems to indicate the trend appears to be slowing down slightly. The numbers at the end of 2022 are still significant and don’t seem to indicate the complete end of the trend.

Understanding what is behind the thousands of people quitting their jobs to move to another company or sector is not just important for recruiters and businesses facing the challenge of holding onto talent, but it’s also relevant to understand how the market and people are changing their perception and relationship with their careers.

Ana is in her thirties, has been living in central London for many years now and is what we can consider a “career changer”, having studied Political Science and Public Administration in Spain but changing her career path to become a software developer a little over three years ago.

Before she switched to tech, she struggled to find a path related to her first choice of studies but felt unprepared and doubtful, so she went on to get a master’s degree in International Economics. Her choice of master’s was a change in itself, but it didn’t help her feel sure about the direction her career was taking.

She mentions feeling confused, regretful of her decisions and a bit lost when her master finished, and she started looking for work.

“I was like, I should have studied engineering, for sure, right? …Yeah “

Going to job fairs after university landed her first job as a recruiter in HR for a tech company in London. It was during this first experience that she discovered she had many things in common with her coworkers that worked on the tech side of the company.

“Ana: It was so nice with them, like, and to hear conversations about what they were doing in their jobs, so yeah…

Hipopotesis: do you think that was a factor that inspired you into switching to tech?

Ana: Yeah, definitely. The environment “

It wasn’t just that she liked everyone at the tech department: she felt curious about programming and saw it as an unexpectedly creative field, where there was much room to grow professionally and an opportunity to work in a team, where she thrives. She thought salaries were high, and she could see many jobs available. At the time, Ana was recruiting a lot of “Java Profiles”, and throughout that process, she discovered that Java was considered “a basic kind of educational language that they teach in order to explain object-oriented programming”.

Ana considers herself interested in learning the foundations of skills, so once coding piqued her curiosity, she decided to start on a short and easy course by City, University of London. This decision helped her feel safer and more in control of the change, as she didn’t feel ready to commit to a full course, quit her job or completely change career paths.

After she enrolled in level one, she found herself completely lost, surrounded by students with some programming knowledge. Still, she didn’t give up and enrolled in level two. By the end of 2019, she felt more confident in her decision to change career paths and informed her boss.

Soundbite:

She switched departments internally and received informal in-job training. Her new boss would send her free online courses, and she worked hard to learn on the go. After three months, the first wave of COVID-19 hit, and she wasn’t offered a position after the internship finished. Ana felt a bit lost after that, not having enough formal training to apply to other jobs and dealing with all the market changes COVID sparked.

Lockdown brought her the opportunity to invest time and energy into her education, and she joined a two-year programme online on programming and software development.

She’s happy as a developer now, engaged in a team and motivated to keep updating her skills and continue learning. She loves that her job requires her to constantly reskill some areas of the skill set and feels like those challenges will inspire and motivate her for a very long time.

Talking about the advantages of being a “career changer” in the tech industry, she mentions that “In the long term, probably, we are gonna be very valuable assets. Yeah, because we have these transferable skills (…). On many occasions. I noticed that I have the big picture of things, really quickly”.

Olivia, also living in London, studied Spanish and Portuguese at university, then did a master’s in translation. She currently works as a publishing house’s localisation project manager but dislikes her job and the editing industry.

That is why she is currently transitioning into tech.

She chose to study Spanish and Portuguese because she had been a good language student in school, studying Spanish and French, and wanted to travel and thought learning languages would be useful for any future job.

Soundbite:

Learning Spanish, for example, proved helpful for her when she decided to move to Spain just after university and worked as a part-time English tutor while also working in a publishing house. Towards the end of 2019, she felt stuck in her career and came back to London to do her master’s in translation, a field connected to languages that could open more doors for her.

Since she finished her master’s, she’s been working full-time in the translation-publishing industry, and her experience hasn’t been positive.

“So many reasons. How long have we got? hahaha (…) Yeah, I think it’s definitely around the working conditions and maybe client expectations because there seems to be this sort of unwritten rule that everything …. well, I think the problem is that clients maybe don’t think about the translation part of their project. If they’re launching a product or whatever, they don’t think about it until the last minute, in which case there’s not a huge budget, I guess left for it and there’s not a huge amount of time. So the kind of projects that I am working on is it was like we have multiple deadlines every day and to be honest, that just got exhausting”

Feeling overworked in her job, working long hours with what she considers a “pretty bad salary, especially for London”, and stressed and toxic work environment have pushed her towards the idea of switching career paths.

The inspiration for transitioning into tech came, in part, from her partner.

Soundbite:

Exploring the idea of this fresh start, she feels tech salaries are attractive, and the job offers she has seen make her feel that the digital tech industry is growing and “I think with a skill like coding, there always will be some sort of job for you.”

Like Ana, Olivia doesn’t want to jump into tech without a safety net, so she has enrolled in a free 60h Udemy class on web development to learn a bit about coding and see where that takes her; she’s not ready to quit her job yet. After the Udemy class, she would like to join an evening course that is also free to have some in-person experience.

“And then I have also considered the in-person boot camp. So I’ve been to open sessions that they do, also little online courses that they do that are an hour and a half, 2 hours, just so you get an introduction. So, yeah, definitely taking steps. Like I say, I think my main issue is that I don’t want to rush into it without properly thinking it through and then say, in two years, oh, I’m not sure this was for me.”

When asked a bit more about the Bootcamps she’s looking into she makes a point of explaining that she is interested in enrolling in a Bootcamp that focuses on women in tech, which is a concern for her. She mentions that some Bootcamps offer scholarships for women getting into tech or that help them find work in companies with more than two or three women in the team. She’s giving herself until the end of December 2022 to decide which Bootcamp or course is best for her.

At this point, her expectations for the future are flexible and open: “I think if there were a position where I could move into the tech industry but still work with languages some way, I think that would be my sort of ideal position. Yeah, I don’t know because at the moment I don’t feel secure enough to say, oh, I’d love to do software development or web development.”

Both Ana and Olivia, as career changers, point out similar reasons to switch to the tech industry and some similar concerns. The abundance of job vacancies, easy access to education and reskilling, and the prospects of a better salary is among the reasons they give for their career change.

A team-work atmosphere and finding a niche in tech that can be creative and motivated are also important reasons for them. At the same time, they are both concerned about the lack of women in the industry and whether or not that can become an entry barrier or an in-job issue.

They are quite correct in their assessment of the industry, and their personal reasons certainly match the growing trend of workers switching to tech. According to the CW Turning to Tech report, IT workers name these as the top advantages of a tech job: high demand for skills, endless ability to learn, rewarding work, career stability and salary benefits.

Ana and Olvia are not alone in pursuing a career that is more flexible, high paying and that prioritises female well-being. A spike in women’s unemployment at the end of 2020 and a noticeably large job-hopping trend in sectors traditionally associated with women (education, childcare, hospitality) has helped shine a spotlight on a trend sometimes called “she-cession”: Many of the “hard-hit” sectors that COVID-19 disproportionately affected are sectors led by women workers, and the gender inequality that stemmed from that impact is still sending shockwaves across the job market.

Skilled women are actively looking for industries and jobs that can provide alignment and safety in sectors with good social and employer support.

Workers, no matter their gender, are looking for careers that no longer require them to give up primary areas of their lives in favour of work, where they can feel connected to a team and work for a company that is aligned with their own values. Look at the State of Work of Slack.

Trends by sectors:

Web development

According to the Office of National Statistics, The UK has one of the highest internet penetration rates in the world. Data shows that there were an estimated 62.86 million monthly users in 2021, and it’s expected to rise to 65 million monthly users by 2026. What’s more, 89% of UK citizens go online daily.

Mobile internet penetration is also notoriously high: In 2022, 92.26% of British people used the internet on their phones, and projections indicate that the number could increase to 94% by 2025. By 2020, the most important device used to access the internet in the United Kingdom was the smartphone.

As the numbers of internet users grow and this lever of digitisation continues to expand, web development will continue to be in great demand in the UK.

The UK population currently uses the internet for just about everything: from shopping to entertainment, education, work or healthcare. All areas of our personal, professional and social lives are affected by the use of the internet. To face this massive demand for internet usage, web and software development in the UK continues to grow and thrive.

To help put into perspective the scale of internet usage, by December of 2022 there were 9,723,483 third-level domains and 1,375,774 second-level domains under management in the UK. Another key statistic to help grasp the volume of internet and site usage is that the UK has one of the strongest e-commerce markets. UK’s e-commerce industry revenue stands at around £2,089.6 billion towards the end of 2022, representing almost 28% of all sales. This unmatched cultural shift challenges in-store commerce and doesn’t look like a fading trend.

This requirement by users and consumers translates into industry growth and job demand. According to Statista, in 2019, there were 386,900 programmers and software development professionals in employment in the UK, which is not taking into consideration almost 198,000 support roles in the software and services sector.

By 2021, that number rose to approximately 466.000. The demand continues to grow: it is estimated that software and web development account for more than 10% of tech jobs advertised with an annual salary that has grown from £57,500 in 2021 to £67,500 at the end of 2022 . The difficulty in recruitment and meeting the market’s demands for talent is driving the salaries up and accelerating fierce competition in the acquisition of talent and in strategies to hold on to it.

Digital trends that we can already experience and predict growing, such as cloud computing, artificial intelligence or data analytics, all require software skills, and it’s easy to predict that the demand for skilled professionals in software development will continue to grow.

Regarding industry trends to keep an eye on for 2023, we will continue to see an interest in cloud computing, web 3, AI, machine learning, metaverse, augmented and virtual reality, Internet of Things and software 2.0. The interest in these fields will not only grow but become more and more essential for everyday internet usage. Rapid innovation is exponentially accelerating technological progress, making each year a big jump in advancement, research and development of tech to come.

For example, according to a study by McKinsley & Company, by 2050, half of today’s work activities could be automated and the working time required for software development and analytics could be 30 times faster.

Other trends to look out for are:

- Low-code/ no-code is also a growing trend for 2023, since it can contribute to faster innovation and faster deliverability.

- Progressive Web Apps, or PWAs, that are easier to create and maintain and also helpful for users.

- A Microservices architecture, an approach that allows teams to achieve greater efficiency and scalability.

- 5G will have a more significant impact in users’ experience of the internet, and they won’t impact only the speed but will also pave the way for technologies like VR or AI to accelerate.

- Cross-platform app development, an approach that enables developers to create apps that can switch between Android and iOS easily, providing a seamless experience for users.

- The Internet of Behavior (IoB) enables a new form of human-machine interaction and is gaining traction quickly.

Data Analytics

According to CompTIA UK Tech Industry and Workforce Trends 2021, data analysis and processing is the second leading tech occupation in the UK, just under software development and web design. The data analyst job description has changed a bit over the last three years: one significant change has been the salary, which has gone from £45,000 in 2020 to £50,000 in 2022.

Data analysis experts are currently in high demand. Yet, the industry is experiencing concerning issues when trying to recruit data profiles, which has become what some experts call “the data skill gap”. According to the Office for National Statistics, there are potentially 178,000 to 234,000 data roles to be filled.

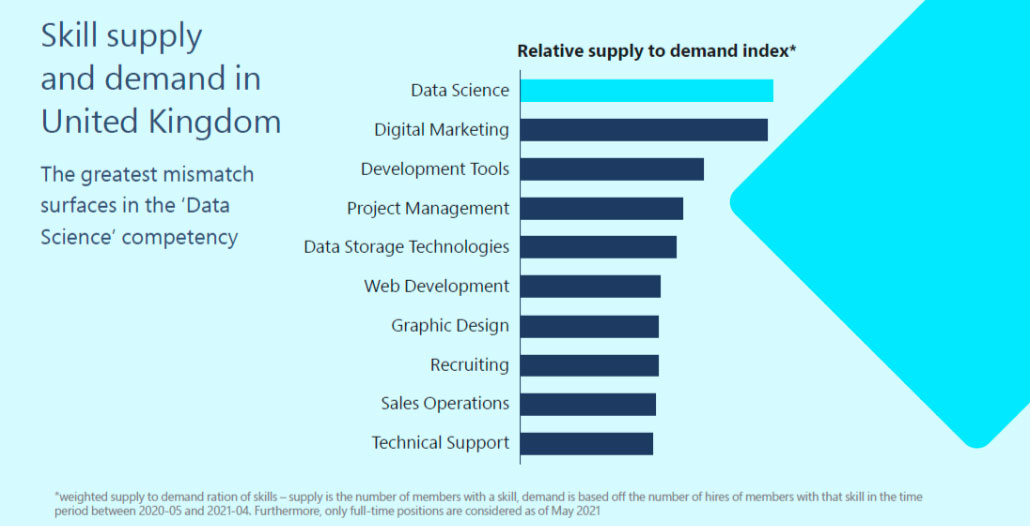

In the Degree + Digital 2022 report, Data science is listed as the top skill in demand in the UK. In this same report, written by Microsoft and using data from Linkedin, the role of universities is examined as a critical point in solving this skill gap, and it is considered inadequate to solve the problem on their own. The estimated potential supply of data scientists from UK universities is unlikely to be more than 10,000 per year, based on data on graduates from UK universities between 2017-2018.

Organisations need to look beyond academia to fill the data roles, turning to upskill and cross-skill people to accelerate the rate they can fill those needed vacancies.

Image from DEGREE+DIGITAL report

The data skill gap is not just a numbers game; the shortage is also heavily influenced by the fact that the right data expert is very hard to come by: someone who is skilled in applying practical applications to their data sets. This is where the demand is highest and talent is lacking.

Over the years, data skills have become crucial for many cutting-edge technologies, and companies are looking to recruit data experts with different skill sets and different goals. It has become less of a routine-based work and is now considered a much more specialised job that requires complex expert thinking and solid communication skills.

What’s more, there are now more industries looking to utilise data for growth, in some cases sectors that a few years ago didn’t really seem all that interested in using data as a resource. Healthcare, security or hospitality are some sectors currently experiencing a surge of interest in transforming how they gather data or how they use it.

The United Kingdom, in an effort to improve its leading role as a data-driven economy, is directing much attention to solving the data skill gap, as it represents a clear threat to the continuity of the UK’s strong data economy. In late 2020, the National Data Strategy was published, where the government recognised the data skill gap and the implications it could have for the entire UK economy and its workforce. Data, as a resource, is considered so valuable that according to the data strategy, “ while not every worker needs to become a data scientist, everyone will need a basic level of data literacy to operate and thrive in increasingly ‘data-rich’ environments”.

During 2023 and upcoming years, upskilling employees in skills needed for data processing, gathering or analysis will become more and more important. Enabling teams to receive basic data skills will also be very relevant as organisations move towards a data-driven culture, where decisions are based on data insights and rely less on “gut feelings”. We can call this culture shift “data democratisation”. Data will, in turn, become accessible for entire teams, empowering them and allowing them to work more efficiently.

Up-to-date data or real-time data is becoming a powerful tool for companies. This live data is sometimes referred to as “Modern Data, » and it’s becoming increasingly important in decision-making processes for consumers and businesses. Sophisticated strategies to manage and extract value from live data result in a competitive edge, but it also requires teams of highly qualified data experts.

Data is also becoming a service (Daas or Data as a service), a resource that companies can access and that can be already gathered, curated and processed. Daas will reduce the need to build data (an expensive venture) and enable companies to use third-party data sets that can be helpful for their decisions, products or users. This data market is steadily growing and could reach 10.7 billion dollars in revenue by 2023.

Data is not only a relevant resource for companies but also a crucial resource for governments, countries, and consumers. Data is an invaluable resource, and its use, importance and value only seem to grow.

UX/UI Design

The PC revolution, the web revolution and great press are the reasons why UX and UI have grown exponentially and are expected to reach 100 million UX professionals by 2050, according to a study by the Nielsen Norman Group.

UX and UI experts are amongst the most wanted professionals in today’s tech market, and it was in the top 10 demanded skills of 2022. The job market for UX and UI design is also incredibly diverse since experts are sought after in a number of different industries, company sizes and teams. The average salary during 2022 was around £55,000.

As the industry changes and evolves, UX designers are naturally evolving with it and adapting to new expectations and challenges. The UX/UI role is becoming increasingly inclusive, requiring a broader skill set and a well-rounded approach, from code, design and leadership to analytics. For these reasons, UX professionals must build a broad skill set to stay competitive in their field. This process of evolution within the industry can feel like the UX/UI definition we currently work with is muddled and starting to dissolve into more specialised areas or new definitions.

This specialisation is already easily observed by looking at UK job listings. Companies are looking for more defined and specific experts: UX/UI combined designers, UX researchers, experts in gestural interfaces, voice-guided UI specialists or interaction designers.

UX and UI professionals are feeling the need to diversify their expertise and newcomers will be expected to get ahead of the specialisation trend by starting their careers with well-chosen expertise they can grow in.

Amongst some trends that are on the rise and are predicted to continue being relevant, we could include storytelling in favour of long scrolling or navigation, micro-interactions, personalisation or using illustrations and emotional feedback to engage users.

Some wider trends that are expected to impact the UX and UI market in the coming years are:

-Minimal to no-contact interfaces that have become incredibly popular in the years after the first COVID-19 wave. Instead of touch, these interfaces rely on voice commands. The use of these kinds of interfaces is expected to grow in public services and in home-used products also.

-Linked to the above trend, there is also a strong push for motion design and gestural interfaces. Users are connecting to devices in a more seamless way, and gestures (pinching, tapping or moving the screen are some examples) are a big part of this human-machine interaction trend.

–VR and AR design is here to stay and expected to flourish in 2023, especially in e-commerce. These technologies change how users interact with digital environments and require UX and UI experts to learn new ways to design engaging and seamless digital experiences.

-Cross-platform development is also a trend that gains traction for 2023 and future years. Experiencing a seamless transition across multiple devices is a must-have for users, and a UX/UI design expert is essential in ensuring that design stays consistent and useful across platforms and devices.

-Accessibility is becoming more relevant as the tech industry struggles to become more inclusive and aware of diversity.

-Working with AI in the UX/UI design process: using AI tools to help cut-down time or assist in organisation and analysis.

Cybersecurity

According to research conducted by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, around 697,000 businesses in the UK struggle to carry out basic tasks that involve cyber security skills such as safely transferring data, updating software or detecting malware. In the same report, an alarming statistic shows that, since 2014, the number of companies reporting a problematic cyber skills shortage has gone from 23% to 51%. In 2022, 39% of surveyed companies in the UK experienced at least one cyber attack, resulting in large money or data losses.

Despite various state-backed initiatives created to improve cybersecurity in the private sector, like, for example, the Cyber Essential Scheme, it’s evident that businesses are finding it hard to develop their basic cybersecurity skills or find talented professionals that can help them. The COVID-19 pandemic also made the cybersecurity skill gap even deeper, and it has been reported that cybersecurity issues went up as businesses adopted remote work.

Cybersecurity is not only a risk for the private sector. In a climate full of geopolitical tensions, cyberattacks are expected to continue as a weapon of choice. The need for talented professionals to fill this market gap is big both in the private and public sectors, and it’s a global problem. Some estimations indicate that there is a global shortage of 3.4 million workers in a workforce that is currently around 4.7 million workers.

Ransomware, malware designed to stop you from accessing files, is one of the biggest threats in cybersecurity and 2023 will not see the trend die down. Tech designed to detect it is expected to become more popular.

Phishing, a widespread cyber-attack, is becoming highly localised, and geo-targeted scams are harder to identify and track. Training and

AI tools in cybersecurity will reduce the human-error factor and help teams prevent attacks and deal with them.

At the same time, some AI tools can represent a threat to security, such as deep fakes or voice recognition. User awareness is expected to grow in the coming years as cybersecurity becomes a more personal concern.

Product Management

A career in Product Management has gained much popularity over the last couple of years, although it’s still considered a fairly new discipline. A trend that has contributed significantly to the awareness of this role is product-led marketing strategies that require a lot of product talent to be successful. Product Managers wear many hats and the role tends to demand a wide skill set, where leadership is often supported by a technical foundation.

The increase in demand for Product talent has resulted in recruitment being especially difficult and salaries jumping up in the hopes of retaining talent and driving it in. The average salary in 2022 was £67,500. The salary growth has created somewhat of a bubble that, as the market settles down and product talent becomes more well-known and more people steer their career in that direction, which could change the responsibilities and expectations of Product Managers. In the future, the role might come with higher expectations, but salaries could stay the same. In the meantime, high salaries and growing awareness incentivise job-to-job hopping in the product management market.

As the role and its demand change, there are several trends for product teams that we can expect to see grow in 2023 and future years:

-Data-driven product management: PMs are incorporating more evidence-based decision-making processes with the help of AI tools and analyses. Paying special attention to the research side of product development is also contributing to the use of insights in management.

-Customer-centric approach to delivering value through products. Product development’s need to remain user-centric and focus on users’ needs and wants will continue to be highly important for consumers and product teams. Understanding consumer priorities is a key part of a Product Manager who can successfully guide a team to deliver a product that can positively impact a user’s life.

-Time and team management continue to be relevant in a market where new forms of work strategies are emerging. Hybrid work, remote work and prioritising work/life balance are all important aspects of day-to-day team management.

Career Development

In 2023 and future years we can expect to see accelerated growth in talent demand in the digital tech industry, and the current tech skill gap we are experiencing will continue to be an issue for recruitment, tech development and economic growth.

The global talent shortage is expected to widen, and the challenges that come with it will continue to present problems for companies, people and nations. However, the skill shortage also brings some unique opportunities for individuals: the tech industry is attractive for those looking to change career paths and continues to drive in new talent with the promise of stable income, a good work environment and an ever-growing industry.

However appealing tech might be for newcomers, those already in the industry must remember to highlight the disadvantages and not contribute to an unrealistic portrayal of the tech sector. It’s important to remain realistic and understand the advantages and disadvantages of tech roles or other non-technical roles in the industry.

Specialisation is a big trend in tech as more roles are no longer so general and mature into more well-defined and specific jobs. This could impact how tech workers continue developing their future careers and how newcomers enter the tech force.

Automation is redefining many areas of work, forcing tech companies and workers to brush up on their skills and the value to add to the market. It will continue shaping the future of the industry, the way people work and the way they consume, how we measure productivity or even how we produce economic value.

New future trends and paradigm shifts

As we begin 2023, it is no surprise that there are many unknowns in the current environment. Economic concerns are prevalent in Europe and the rest of the globe, and political tensions and resource management continue to be major sources of uncertainty and conflict.

The tech industry is not isolated from these worrying global trends, and it’s been severely impacted by them. The future of tech in the UK and the world is directly linked to new social movements, sustainability and economic alignments. Being such a substantial industry that affects almost all areas of life, the tech industry can’t be separated from cultural and social shifts: our global priorities affect the tech market and shape its development and future.

The UK is strategically working towards consolidating its position as a tech superpower in the world, devoting many resources and talent to this long-term goal. On a geopolitical level, the UK’s top priority is to ensure that its tech industry is adequately connected to other global tech players. This is necessary for market growth, remaining attractive for the rest of the market, talent acquisition and successful expansion of the UK’s role as a data-economy leader. In a post-Brexit scenario, a priority for the UK is to consolidate its role in a European tech market while establishing alliances with other nations without Europe’s regulations or guidelines. Aside from the government’s optimistic approach, changes in the regulatory environment will continue to rock the industry and elevate the feeling of uncertainty.

The industry, in global terms, is settling into a more conservative approach to growth. Layoffs, downsizing and shifting how teams are located have become significant concerns for the market and have dampened some optimism in the industry. Growth is no longer valid at all costs, particularly when people’s jobs are on the line, and this newfound perspective is transforming how many people view their careers in tech and prepare for the future.

The phenomenon dubbed “the great resignation” has made obvious a large portion of the industry is not willing to sacrifice many of their life priorities for the sake of their current company, and they are happy to change jobs in the hopes of finding an employer that can offer the benefits and safety they want. This massive social and cultural trend is not disappearing, and some research indicates that new generations to join the workforce will do so with clearer expectations, demands and boundaries.

Tech workers have adopted some advantageous changes the COVID-19 pandemic brought us, the most important being remote and hybrid work. This way of working is not a passing trend, and it’s presenting challenges that tech professionals need to adapt to in order to remain relevant in the industry, both as employers and employees: the future of tech is hybrid.

Towards the last half of 2022, some advancements in AI and other technologies have sparked urgent conversations about ethics in the tech world, the role of human tasks in the market and how we can prepare ourselves to face new challenges and adapt to rapid changes. The conversations surrounding tech ethics, human-machine relationships in fields like art, education or research, and the implications of new tech in many areas are far from over. In 2023 and future years, we can expect to have deeper discussions surrounding accountability, ethical progress and human safety in the face of a massive tech paradigm shift. As mentioned before, these discussions and debates are mainly social and cultural, so they can’t be examined only from a tech perspective.

Conclusions

The UK holds a relevant position amongst key tech players of the world: it has a strong digital infrastructure, a growing technology industry, valued at just under $1tn , a thriving startup scene and detailed plans to become the top data-driven economy of the world. The UK’s digital strategy aims to create a guideline for the UK’s future digital transformation and digital economy, and to strengthen its position as a global Tech Superpower.

As impressive as the UK’s leading position may be, its still facing significan challenges before achieving its digital objectives. The COVID-19 pandemic and its present effects still have considerably impact over the UK’s social and economic structures, and highlighted how crucial digital skills are for al citizens.